Subscribe now and get the latest podcast releases delivered straight to your inbox.

It’s a peculiarity of economics that the best product doesn’t always win. Even if the quality is better, the other parts of the equation might not be.

Maybe the timing is wrong. Maybe the marketing goes awry.

Maybe the marketplace is already dominated by heavyweights boasting solid brand loyalty and customer retention.

In order to really take the market by storm, everything needs to line up properly. If it doesn’t, you end up as a footnote, a punchline, an afterthought — if not totally forgotten.

In some cases, these failed products and services fill marketing and economics classrooms and textbooks as case studies.

What went wrong with Beta Max? Why did Crystal Pepsi fail?

For each of these products, consumers down-voted them with their dollars.

In the digital world of social media, consumers vote with their virtual feet.

The early social media landscape

In the early days, now-defunct social networks like Friendster and MySpace were hugely popular, only to be abandoned by users migrating to Facebook.

If you’re mesmerized by bar graphs like I am, check out this rendering of the market struggle:

You probably noticed “Google+” (or “Google Plus,” as we’ll refer to it in this article) appear in the fray, climbing up a few spots before falling off entirely — right around the time Facebook passed 1.5 billion users.

How did Google, which seems so prescient in most things digital, fall short and get social media so wrong?

The story starts nearly a decade ago.

What was Google Plus?

Google Plus was not Google’s first attempt to enter the social media landscape. Other failed attempts had come before it (anyone remember Google Buzz?), but in the summer of 2011, Google launched Google Plus hoping to stand out from the competition.

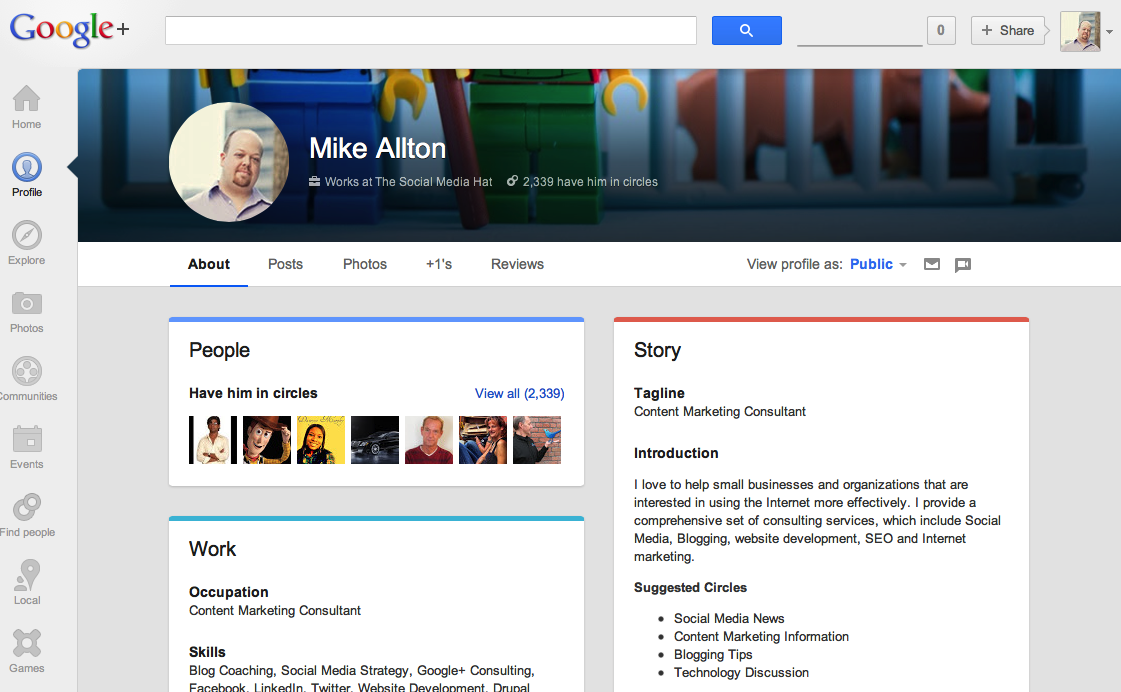

The platform featured a publicly-visible, real-name-required profile page featuring an image and basic information. Users connected to others by creating “circles” of coworkers, family, or those with shared interests.

Here’s what it looked like:

According to the New York Times, “Google Plus was meant to be a Facebook competitor that linked users to various Google products, including its search engine and YouTube.”

With the launch, Google was attempting to attack Facebook head-on by moving into Facebook’s turf.

The platform had become the world’s largest social media site by this time, having squashed each of its competitors — and it showed no signs of slowing down.

Google, for its part, had been on top of the search engine world for a decade by 2011, owning roughly 63% of all searches. (For comparison, today Google comprises about 92% of all searches.)

By the time it launched Google Plus in 2011, Google also owned YouTube and offered Gmail, which was about to pass Hotmail to become the world’s most used email service.

With two such powerful players, perhaps a conflict was inevitable.

Google believed a social network would unite users’ internet experience and assert the company’s dominance.

For Facebook, Google Plus represented, according to former product manager Antonio Garcia Martinez, an “existential threat comparable to the Soviets’ placing nukes in Cuba in 1962.”

Martinez continues, writing in Vanity Fair: “Google Plus was the great enemy’s sally into our own hemisphere, and it gripped [Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg] like nothing else.”

As Facebook mobilized and came to grips with a well-funded competitor, Google put its full weight behind its new effort.

Google Plus at full strength

According to Martinez, Google co-founder Larry Page, speaking at a company-wide Q&A in January 2012, was resolute about the company’s commitment to Google Plus: “This is the path we’re headed down — a single, unified, ‘beautiful’ product across everything. If you don’t get that, then you should probably work somewhere else.”

Google imagined Google Plus functioning as a unifier across the internet. When using Gmail, when watching YouTube, when following Google Maps, when downloading in Google Play — a user’s Google Plus account would be a seamless structure underpinning it all: “a social layer across Google products,” according to TechCrunch.

But Google stumbled in its quest to unite the entire internet under its multicolored umbrella.

Google Plus and business

In what now seems like a towering blunder during the 2011 launch, Google initially forbade all businesses from having profiles on Google Plus.

At the launch, some businesses complied, some didn’t. Some had their accounts suspended, only to be reinstated later. Other businesses disguised their corporate pages as personal pages in order to access the burgeoning network.

And this was all within the first few weeks of launch.

In November of 2011, Google launched Google Plus Pages, which allowed businesses to build profiles and connect with customers.

Eventually, Google merged several features, including Google Plus Local, Google Maps results, and ratings from Zagat, which it acquired in the fall of 2011.

Like business pages on other platforms, these features and pages gave organizations an opportunity to establish a presence where their audiences were spending time, to share offers, and to drive traffic to their websites.

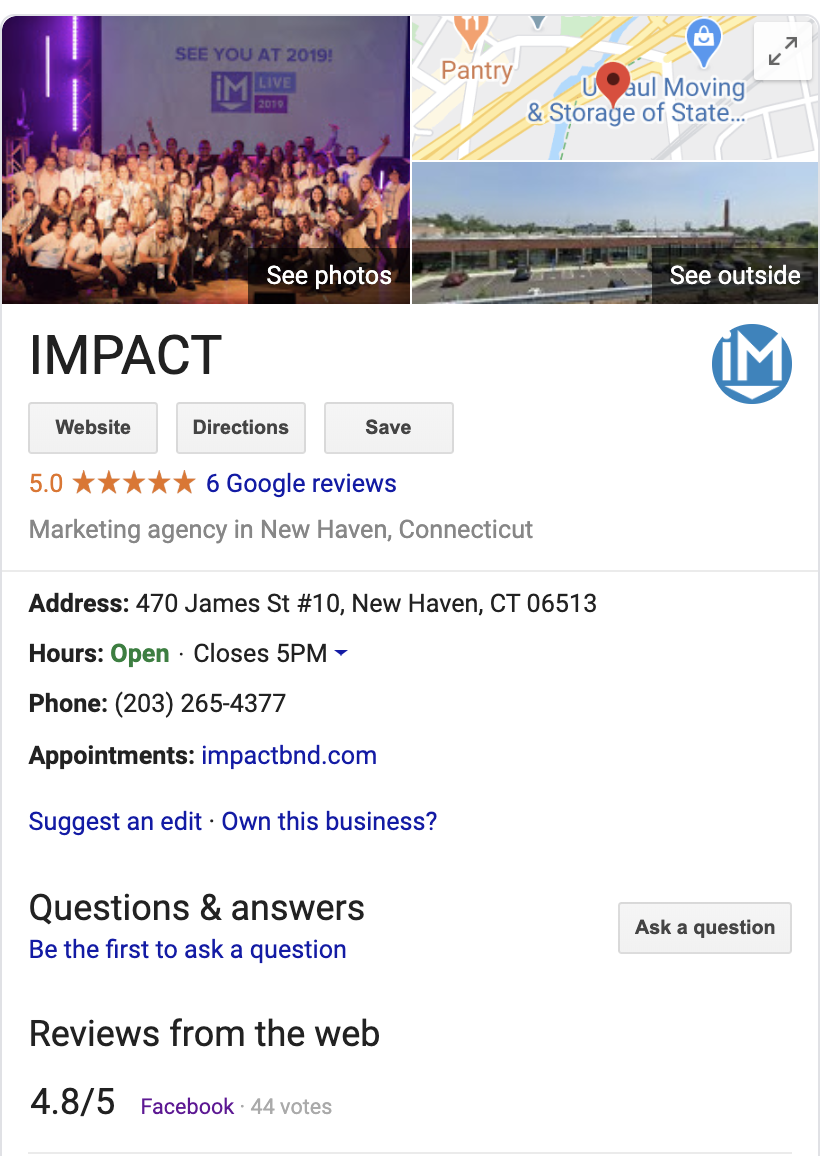

This became the Google My Business feature we know and use today.

The decline and fall of Google Plus

By early 2012, despite approaching 100 million users, Google Plus was still lagging significantly behind Facebook, which had nearly a billion.

Google was eager to capture any engagement it could, even if that came by force.

In 2013, the tech giant declared that users could only comment on YouTube videos with a Google Plus account — and started automatically creating Google Plus profiles when a user signed up for Gmail.

Many saw this as overreach.

At the same time, some associated products and services failed to gain traction. People still preferred Skype to Google Hangouts, for instance.

And Google Plus itself, despite gaining users through other Google services, was not seen as a compelling online hangout.

Google Plus had the worst of problems: As many as 500 million users, very few of whom actually engaged with the site on a regular basis.

In the spring of 2014, Google Plus’ head, Vic Gundotra, abruptly left the company, and the Google began to dissolve the mandatory connections between its products.

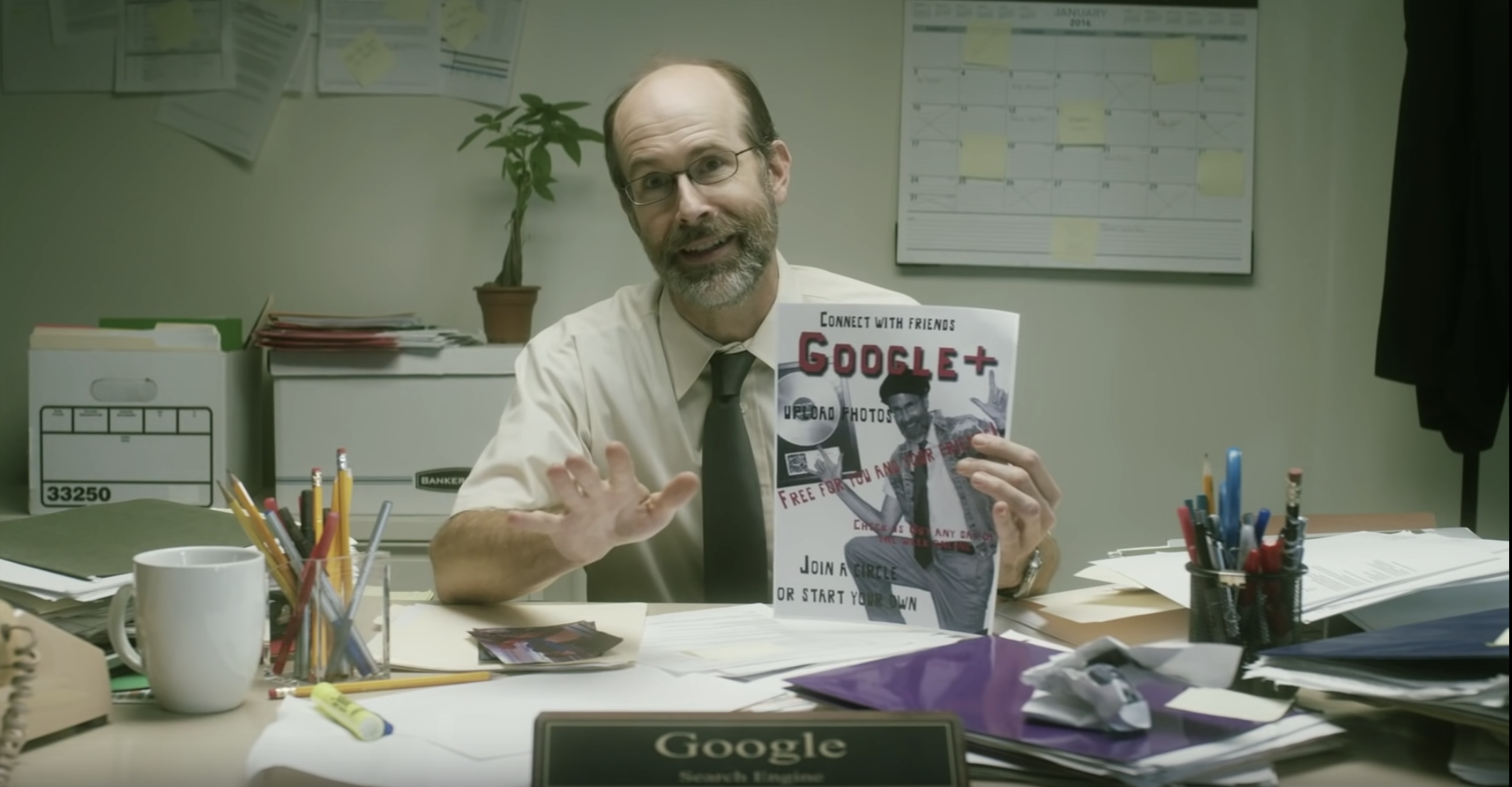

Soon, Google Plus became a punchline, as in the College Humor “If Google Was a Guy” sketches:

Google Plus shutdown

Although Google declared its intention to maintain its investment in the platform, engagement continued to decline.

In March of 2018, Google discovered a security flaw that could allow users’ data to be accessed by outsiders. After sitting on the information for a few months, Google announced the official shutdown of Google Plus in October of that year.

The company put it this way: “Given these challenges and the very low usage..., we decided to sunset the consumer version of Google Plus. To give people a full opportunity to transition, we will implement this wind-down over a 10-month period, slated for completion by the end of next August [2019].”

Google My Business for marketers

Just as the Space Race of the 60s yielded Velcro and Tang — among other more historic accomplishments — Google Plus’ race for social media dominance gave us technology and products that live on today.

According to Blue Corona, “Google+ never really took off as the social network Google wanted it to be, but it’s still critically important to local businesses. That’s because the information in Google+ is what customers see when using Google Search or Google Maps.”

Although it’s no longer branded as such, Google My Business (GMB), which likely serves as a focal point of your business’ online presence, is a vestige of Google Plus — and vital to getting found and indexed by the search engine.

According to our own Kevin Philips, IMPACT’s lead content marketing trainer,

“An optimized GMB page helps Google understand more about your business: who you are, what services/products you sell, where you’re located... and what your website is (so they can crawl it for more info). The more Google knows about you, the more types of searches your GMB listing can appear in.”

GMB is especially crucial for local or brick-and-mortar businesses, as Google typically takes a searcher's location into account when delivering results.

Prudent leveraging of GMB should be part of any business’ marketing strategy in 2020 and beyond.

The way things came to pass: Lessons learned from Google Plus

Today, when we think of the biggest forces of the tech world, we tend to always mention the same four companies: Google, Facebook, Apple, and Amazon. In print, you sometimes see these referred to as The Big Four.

For the most part, these firms each seem to stay in their lanes.

Sure, you can shop through Facebook, and Google and Amazon have released phones — but for the most part, Google is search and information, Facebook is social media, Apple is product and software development, and Amazon is e-commerce.

When these boundaries rub up against each other and chafe, however, they can become battle lines.

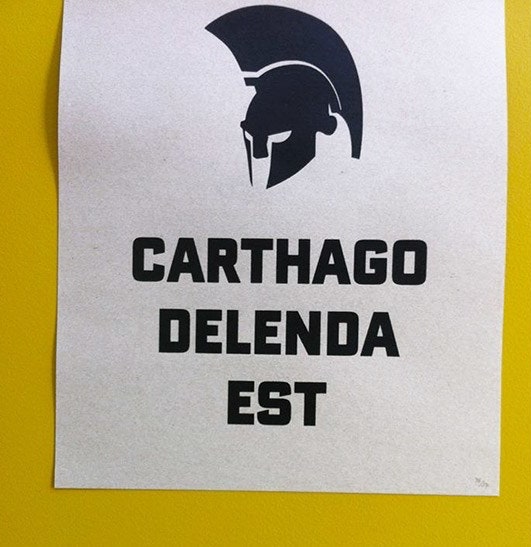

According to Martinez, when Mark Zuckerberg announced Facebook's strategy, he “erupted with a burst of rhetoric referencing one of the ancient classics he had studied at Harvard and before. ‘You know, one of my favorite Roman orators ended every speech with the phrase Carthago delenda est. “Carthage must be destroyed.” For some reason I think of that now.’”

Posters with this phrase were put up around the Facebook offices.

Source: https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2016/06/how-mark-zuckerberg-led-facebooks-war-to-crush-google-plus

When companies live in the same neighborhood and frequently compete for top talent in the hiring process, one can expect bruised egos, simmering tension, desertions, and, occasionally, epic tales of head-to-head combat over market share.

In 2018, it was Facebook who hoisted its banner, victorious.

Whether you see Google Plus as a cautionary tale of hubris and overreach, or a failure of marketing, strategy, or UX will depend on your individual perspective.

Although it is gone today, it lives on in certain ways — and you access it every time you update your GMB profile.

While the platform is gone, we still use “Sign in with Google” on many websites, and our Gmail accounts still allow us to comment on YouTube videos and smoothly open Drive folders.

So, while Google’s vision of ruling over a seamless internet never fully came to pass, its efforts were not totally in vain.

I suppose Google will have to settle for near-total domination.

Free: Assessment