Subscribe now and get the latest podcast releases delivered straight to your inbox.

Website accessibility: Is your company at risk for an ADA-compliance lawsuit?

By John Becker

May 4, 2020

In the summer of 2012, the National Association of the Deaf filed a lawsuit against Netflix. At the time, Netflix had been streaming video content for about five years, but it had not yet dipped its toe into making original content.

While it was not yet the Academy Award-winning-juggernaut it is today, Netflix in 2012 was a sizable company with a dominant presence in the marketplace.

In the lawsuit, the National Association of the Deaf alleged that Netflix was discriminating against deaf and hard-of-hearing customers by not providing closed captions on all of its programming. As such, these patrons were not able to enjoy the service to the same extent as those without a disability.

According to the court filing, the plaintiffs alleged that Netflix’s “failure to caption all of its streaming library violates the ADA’s prohibition of discrimination on the basis of disability.”

This case, which was decided in Massachusetts District Court by Judge Michael Ponsor, represented an important step in the broadening litigation around the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the digital age.

Now, however, years later, the central question of the lawsuit surrounding website accessibility is far from settled.

What is the Americans with Disabilities Act, and what questions did it raise?

The ADA was signed into law in 1990 by President George H.W. Bush. The signing took place on the south lawn of the White House on a beautiful summer day.

The intended result of this monumental legislation was to allow Americans with disabilities to more easily gain access to places of business, worship, education, and government.

(Although the Civil Rights Act was passed in the 1960s under the Johnson administration, it did not extend protections to people with disabilities.)

The ADA standardized and codified practices relating to access and anti-discrimination for citizens with a host of disabilities.

When most people today think of the adoption of the ADA, they picture only the most conspicuous results of the law: wheelchair ramps added to buildings and sidewalks.

In truth, the legislation’s repercussions were extremely far-reaching, and a wave of lawsuits flooded the courts as advocacy groups and companies disagreed on the ADA’s application and reach.

At the crux of these debates was the ADA’s promise “relating to nondiscrimination on the basis of disability by public accommodations and in commercial facilities,” known as Title III.

The question, then, became, what is a place of “public accommodation”? And just what is a commercial facility?

The answer, as it turns out, is still an open question of law.

Here’s why: In a 1994 case that has been cited many times since, a district court ruled “that ‘public accommodations’ are not limited to physical structures.” For example, a phone service could be a place of public accommodation.

Then came the internet — and with it came a slew of new questions around the ADA.

At the center was this: Is the internet a public place?

Why is the relationship between the ADA and the internet so murky?

The internet has fundamentally changed the way most consumers interact with businesses. In turn, it has brought new applications to the ADA:

Is a website a place of public accommodation?

And, by extension, must a website be accessible for people with disabilities?

An early prominent case addressing just this question involved Target and its website. If Target had to make its store accessible for people with disabilities, did it also have to make its website accessible?

In this 2006 case, a district judge in California ruled that the Target website “is heavily integrated with the brick-and-mortar stores and operates in many ways as a gateway to the stores.”

In other words, because the Target website was so closely associated with a physical store, ADA protections would extend to the website.

Thus, Target needed to make its website accessible to people with disabilities.

So, how would judges rule in the case against Netflix, which has no brick-and-mortar store? After all, there’s no local Netflix branch you can drive to if you want to check out a DVD.

In its defense in the case from 2012, Netflix’s lawyers argued that the streaming platform was not a physical place — and therefore not subject to ADA compliance.

In his decision, Judge Ponsor cited an earlier, pre-internet circuit judge’s ruling: “It would be irrational to conclude that persons who enter an office to purchase services are protected by the ADA, but persons who purchase the same services over the telephone or by mail are not. Congress could not have intended such an absurd result.”

Judge Ponsor argued that, “In a society in which business is increasingly conducted online, excluding businesses that sell services through the Internet would ‘run afoul of the purposes of the ADA and would severely frustrate Congress’s intent that individuals with disabilities fully enjoy the goods, services, privileges and advantages, available indiscriminately to other members of the general public.’”

Here, he quotes from the 1994 case mentioned above, borrowing language directly from the decision.

Judge Ponsor noted that the internet and web-based services “did not exist when the ADA was passed in 1990 and, thus, could not have been explicitly included in the Act, [but] the legislative history of the ADA makes clear that Congress intended the ADA to adapt to changes in technology.”

Netflix argued that a customer’s home (where they likely would be using Netflix’s service) was not a place of “public accommodation.”

In response, Judge Ponser wrote that the ADA “covers the services ‘of’ a public accommodation, not services ‘at’ or ‘in’ a public accommodation.”

He argued that “this distinction is crucial,” and it allowed him to conclude the following: “while the home is not itself a place of public accommodation, entities that provide services in the home may qualify as places of public accommodation.”

As such, the court ruled against Netflix, deciding that the platform was subject to ADA compliance. In turn, Netflix was forced to add subtitles, and this corner of the internet became more accessible than it was before.

What are the current statistics around Americans with disabilities?

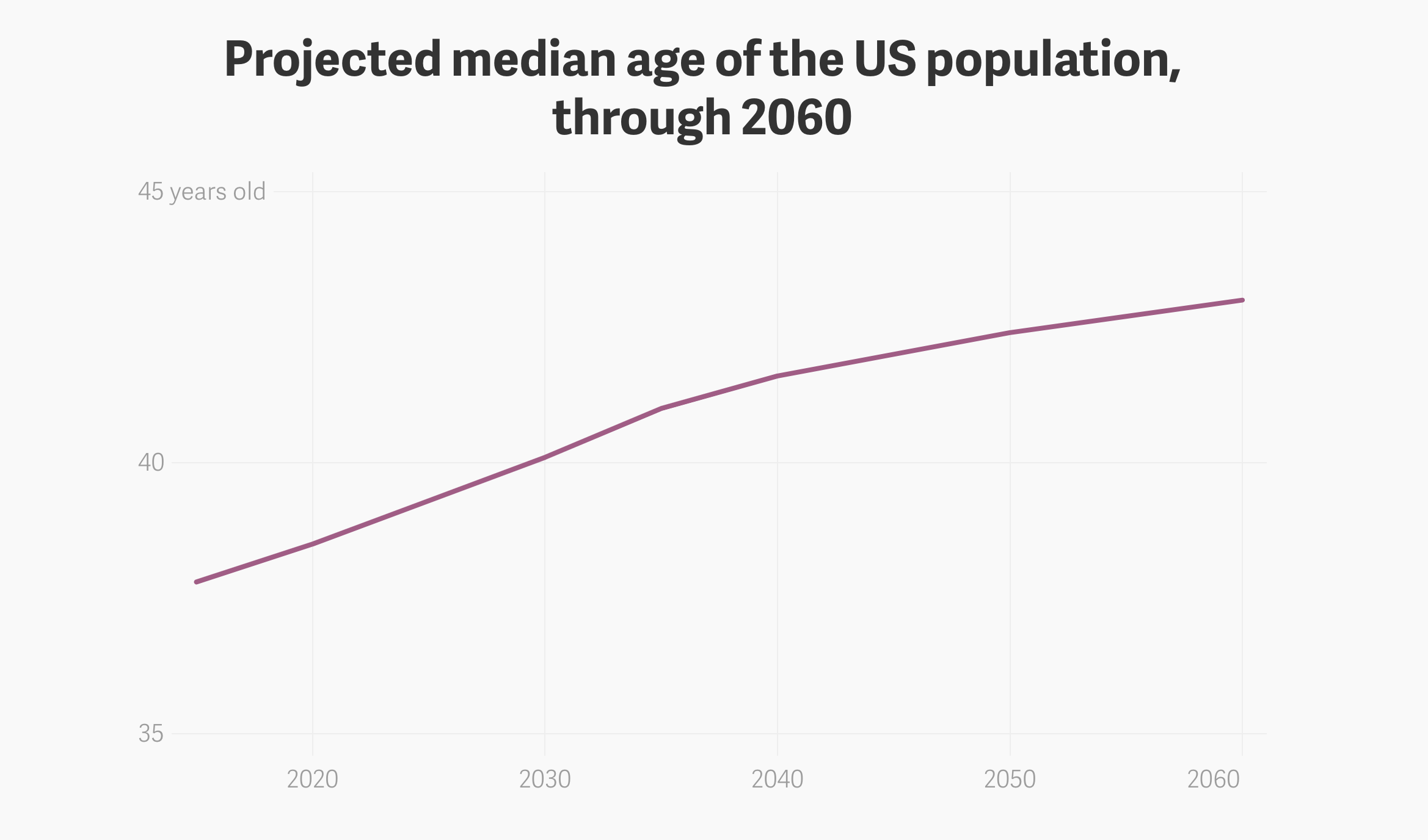

The United States’ population is aging. According to The Urban Institute, “the number of Americans ages 65 and older will more than double over the next 40 years, reaching 80 million in 2040.”

According to the CDC, the birthrate in the US is the lowest it’s been in more than 30 years.

As the Baby Boomer generation ages and retires, and the population continues to skew older, the country will experience an aging demographic unlike anything it has seen before. Increasingly, these citizens are likely to experience disabilities and physical struggles that impair their abilities in everyday functions.

This generation expects internet access (indeed, they invented the internet), and any barriers that hinder that access could be challenged.

But of course, disability is not limited to elderly citizens. Americans of every age, creed, and color struggle with physical, emotional, and mental impairments that might hinder their access to the internet.

According to the 2010 census, 56.7 million Americans are living with a disability. That’s almost 20% of the entire population.

According to Interactive Accessibility:

- 19.9 million (8.2%) have difficulty lifting or grasping that could, for example, impact their use of a mouse or keyboard

- 15.2 million (6.3%) have a cognitive, mental, or emotional impairment

- 8.1 million (3.3%) have a vision impairment and may rely on a screen magnifier or a screen reader — or might have a form of color blindness

- 7.6 million (3.1%) have a hearing impairment and may rely on transcripts and/or captions for audio and video media

To put this in perspective, we’re talking about 50 million people — in the US alone — and these people are using (or attempting to use) the internet in huge numbers.

According to a study from Google (with data from the World Bank and the CDC), “there are more hard-of-hearing users in the United States than the population of Spain and more users who are blind and low-vision than the population of Canada.”

If there are so many millions of people seeking and struggling with access, shouldn’t we work to make sure access is granted?

From a business standpoint, it seems ludicrous to allow barriers to access to exist for such a sizable population.

From a moral standpoint, excluding anyone from our goods and services seems indefensible.

If we all agree that we should make our websites accessible for users with disabilities, why are so many companies behind when it comes to compliance? As it turns out, the devil is in the details.

What are the irregularities of America’s legal landscape pertaining to the ADA and websites?

If you, as a US citizen who lives with a disability, go to your state and claim that a certain website discriminates against you because you cannot access its features, your government official can take an enforcement action against that business.

In 2018, the most recent information available, there were at least 2,258 federal website accessibility lawsuits, which represented a 177% increase from in 2017, according to Seyforth Shaw LLC, a law firm that tracks such cases.

According to Ryan Wieland, a senior account executive at Accessible360, an increasing number of these lawsuits target small businesses. And, in Wieland’s experience, the vast majority of business websites are not fully accessible for all users.

They’re not even close.

In almost all of these cases the end result is a settlement, not a trial. If businesses are the subject of a lawsuit regarding their website, they see a settlement as the quickest, cheapest way out of their predicament.

If the case makes it in front of a judge, the plaintiff who wins in court is entitled to both injunctive relief and recovered attorney fees. For businesses, the latter part of that sentence is alarming — and is the reason so many cases end up as settlements.

Should a customer bring a complaint against your business and, should a court decide in the customer’s favor, you could find yourself with huge bills to pay.

Not only will you have to address the accessibility issues of your website — and fairly compensate the plaintiff for the inconvenience — but you will also have to pay fees for both sets of attorneys, which would likely be the most expensive part of the whole affair.

However, the courts are far from monolithic in their application of the ADA in the age of the internet.

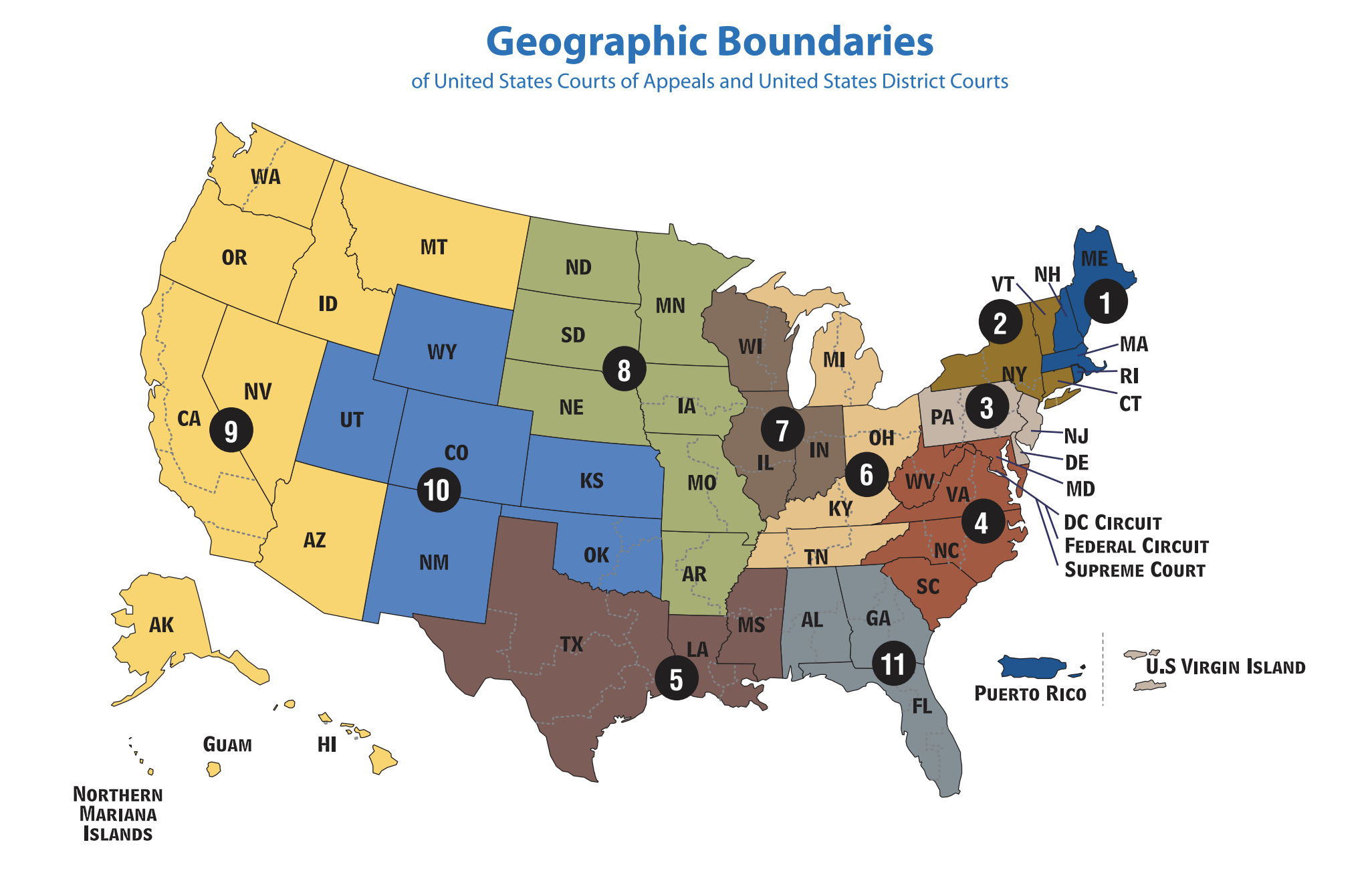

According to an attorney I spoke with, the 1st District Court of Appeals, for instance, tends to have a more expansive reading of the law. By contrast, other federal appellate courts read the law more narrowly.

The courts can’t agree which sites need to be accessible — just sites that are connected to a physical store, or all sites (even if the company has no physical point of sale or service).

According to the American Bar Association, “the Sixth, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits hold that for a website to be subject to the ADA, there must be a ‘nexus’ between the challenged service and the physical place of public accommodation.”

In other words, Target should have to be accessible because there is a physical store. Netflix does not need to be accessible because there is no physical store.

But wait, didn’t Netflix lose its case in district court on these exact grounds?

You see the confusion.

This, right here, is the sticking point. Does your website need to be ADA-compliant? Well, if you live in certain parts of the country, the ADA should only apply to websites that are close extensions of a physical store. In other parts of the country, all websites should comply with ADA regulations.

However, the internet adds another layer of complexity.

Just because your business is headquartered in one location does not mean your customers are right down the street.

What happens if your business is in Alabama but the customer who accesses your site is in Maine? Or, what if they’re from Maine but accessing your site at their vacation home in North Carolina? If that customer alleges that your website is discriminatory, which court will hear the claim?

The short answer: It depends.

According to Whittier Law School professor Betsy Rosenblatt, “Before a court may decide a case, the court must determine whether it has ‘personal jurisdiction’ over the parties.”

However, “The Supreme Court has not discussed the impact that technology might have on the analysis of personal jurisdiction.”

While lower courts have addressed the issue in numerous cases covering a variety of complaints and crimes, “they diverge widely as to whether the presence of [a website] will lead to specific jurisdiction over the party for the purposes of disputes arising from the website.”

In other words, there is a frustrating lack of clarity over just which court might have jurisdiction in any given case.

Then, on top of questions of jurisdiction, any court is made up of a number of judges, each of whom will have a unique outlook.

To make matters even more confusing, the ADA has not been comprehensively updated to fit the internet age.

“We respectfully urge you to to help resolve this situation as soon as possible...”

Federal updates to the ADA have failed to directly address this question. In 2015, the Department of Justice issued a statement that concluded with these lines:

“The Department is planning to amend its regulation... to require public entities that provide services, programs or activities to the public through Internet web sites to make their sites accessible to and usable by individuals with disabilities.”

However, the amendments never came.

In 2018, more than 100 members of Congress wrote to the DOJ asking for “guidance and clarity with regard to website accessibility under the Americans with Disabilities Act.”

Representative Ted Budd, from North Carolina, was the lead author of the letter. He wrote that “unresolved questions about the application of the ADA to websites as well as the [DOJ’s] abandonment of the effort to write a rule defining website accessibility standards, has created a liability hazard that directly affects businesses in our states and the customers they serve.”

At issue were the many website accessibility lawsuits, some genuine and some not, facing America’s small businesses.

Later, 19 state attorney generals sent a similar letter to the DOJ.

Then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a response that further muddied the waters:

“Absent the adoption of specific technical requirements for websites through rulemaking, public accommodations have flexibility in how to comply with the ADA’s general requirements of nondiscrimination and effective communication. Accordingly, noncompliance with a voluntary technical standard for website accessibility does not necessarily indicate noncompliance with the ADA.”

In other words, companies have “flexibility” when it comes to website compliance, which is “voluntary” until more rulemaking takes place.

Being that our congress seems to have its hands full with other matters, and that Jeff Sessions has since been replaced, ADA compliance remains an open question of law — even as the lawsuits pile up.

The truth is that the ADA is being abused.

While true, fair, universal internet access should be the concern of all citizens and the focus of government action, there are those who bring contrived lawsuits against companies for the sake of making a quick buck.

Without clarity from the federal government as to how to apply the law — and how to distinguish between legitimate and spurious lawsuits — the spirit of the ADA becomes muddled.

So, what does it take to make your website accessible and ADA-compliant?

The problem is that no complete, exhaustive regulations have been released to clarify this question.

(There is a well-known 2018 federal update referred to as the “Section 508 update,” but this applies to the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, not the ADA. However, the Section 508 update requires that all “programs and activities funded by federal agencies [must] be accessible to people with disabilities, including federal employees and members of the public.” As such, this does not apply to private businesses.)

Even so, there are best practices that are universally accepted.

With modern screen readers, voice search, and other hardware and software solutions, the internet is more accessible than ever. However, according to IMPACT’s Morgan VanDerLeest, developers should keep several things in mind as they build sites:

- Use of color and contrast should ensure text is readable. For example, make sure not to have dark text on a dark background or light text on a light background.

- The website should be usable without a mouse. Users usually do this by using the tab key to navigate the website. Something to consider is adding a “skip to main content” button so users can jump past the global header of your page. This way, they don’t have to press the tab key too many times just to get to the first hyperlink in your text.

- Include appropriate alt text on images, videos, icons, and other media so no necessary information is excluded from users with screen readers.

- Documents must be structured in a clear hierarchy with standard header tags and sub-headings.

- Have indicators or descriptive text to ensure user interface elements like buttons and links are understandable out of context. For example, instead of saying “Click here,” your button should say something actionable like “Learn about our products.”

- Add appropriate mouse point gestures. Use the pointer icon when hovering over a clickable element and a hand icon when the element can be dragged and dropped. In addition to mouse gestures, add other visual cues for interactive elements such as a change in color of a button when it’s hovered.

According to IMPACT Senior Developer Tim Ostheimer, who works on sites for hundreds of businesses of various sizes, ADA compliance is becoming more and more commonly discussed in the conversations between developers and businesses.

Tim says:

“Discussions around ADA compliance are definitely more common than they were a few years ago. Since these requirements are still changing and expanding, there are some companies that want to ensure they’re up to standards as soon as they can be rather than waiting for it to be legally required.”

Accessible360 is a well-known and well-respected business that works with hundreds of companies each year to make their websites more accessible.

They perform audits and offer consulting services, and possess deep knowledge of ADA regulations, such as they are, as well as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG).

(The WCAG standards, first published by the World Wide Web Consortium in 1999 and updated, most recently, in 2018, provide greater clarity and standardization around questions of accessibility. They are internationally recognized, but are only guidelines and are not legally binding.)

Senior Account Executive Ryan Wieland agrees that more and more of his company’s work is being done preemptively. Still, though, many companies come to Accessibile360 after being the subject of a lawsuit.

If you’ve not been sued, Wieland recommends having a live-user accessibility audit performed on your site, along with periodic re-checks.

These could be as often as once a quarter, if your site changes frequently or has a significant number of product pages. (It's worth noting that about half of all accessibility lawsuits are brought against e-commerce sites).

For most companies, every six to twelve months is sufficient for a check-up.

What should you do if your company is named in a website accessibility lawsuit?

If your business does get sued by a plaintiff regarding ADA compliance, you have a few options. Most businesses choose to pay a settlement, but this does not relieve them of the danger of being sued again.

Again, these cases rarely go to a judge to be decided. Usually, the lawsuit ends in a settlement to avoid the prospect of a lengthy and expensive court case.

If your site is non-compliant and you’re advised to pay a settlement, don’t panic. In most settlement agreements, you will typically have 12-18 months to bring your website up to code.

The process of remediation will likely begin with an audit from a company like Accessible360. Next, you’ll need a developer (either in-house or contracted), and a good deal of patience.

It behooves you to be methodical. Many companies only partially fix their websites (or, even worse, pay the settlement, hoping it will make the problem go away) only to be sued again by a new plaintiff soon after.

According to Wieland, Accessible360 has many clients “that come to us after they’ve been sued four or five times.”

They might settle after the first lawsuit, and do nothing to make their websites more compliant. Then, several months later, a different plaintiff files a very similar lawsuit and the process begins anew.

Thus, careful, focused site improvements are the best way forward — paired with routine audits.

The possible consequences of ignoring accessibility issues can be costly. Some companies that are sued have only a handful of employees. In turn, they may be forced to shut down their website or, even, to close their business.

That’s why, increasingly, companies are being proactive.

Tech giant Google turns toward accessibility

At its most idealistic, the internet is about the removal of barriers. From its earliest days, the convenience offered by now-simple applications like email were touted by the founders of the web.

According to The Guardian’s report on Tim Berniers-Lee, the man widely considered the founder of the internet, the earliest manifestation attempted to “demonstrate a profound concept: that any person could share information with anyone else, anywhere.”

Applied broadly, this philosophical underpinning of the internet advocates for access for all.

Centuries ago, widespread commercial printing expanded the reach of literacy and, in turn, yielded a more educated global population. Historians have credited everything from the rise of the Renaissance to the toppling of monarchies to the printing press and the diversification and dispersion of knowledge it offered.

We have seen similarly broad and momentous social change come by way of sweeping internet access.

Google, which always seems eager to lead the tech world, has taken significant strides to broaden access to its services.

Source: Google

Google began with a simple declaration: Everyone should be able to access and enjoy the web. We’re committed to making that a reality.

In the last year, that has included adding American Sign Language to its support service, releasing Live Transcribe and Sound Amplifier to make audio content more accessible, and debuting Accessibility Scanner, which allows users to easily make suggestions for improvements to Android apps.

Even more recently, Google Assistant can now read web pages aloud — even translating them into 42 languages — on Android devices.

Google also works with the FCC and other government and NGO groups to advocate for web accessibility.

Google's commitment to universal web access should inspire other companies to follow suit.

However, not every firm has the immense capital to fund such initiatives.

ADA compliance, as you would imagine, costs money. Absent a clear set of directives from the federal government, many companies are avoiding paying extra to make their sites compliant.

After all, how many wheelchair ramps would have been built were it not for the law requiring them?

And there is always something that pushes time and resources elsewhere. COVID-19 was only the most recent example.

What will ADA compliance look like in 2021 and beyond for the internet?

Former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, writing a majority opinion in 2017, posited the following:

“While we now may be coming to the realization that the Cyber Age is a revolution of historic proportions, we cannot appreciate yet its full dimensions and vast potential to alter how we think, express ourselves, and define who we want to be. The forces and directions of the Internet are so new, so protean, and so far-reaching that courts must be conscious that what they say today might be obsolete tomorrow.”

To put it more succinctly, it is beyond our abilities to imagine how monumentally the internet is changing every aspect of life.

In order for those changes to equally influence all US citizens, we must do what we can to ensure that the benefits of the internet extend to those whose disabilities inhibit their use.

However, without clear federal regulation, businesses will be left guessing as to what sort of access they should provide, and balking at the associated cost — and they will continue to be targeted by unscrupulous lawsuits.

With no substantial recent updates to the ADA to offer clarification, it seems likely that confusion and litigation will remain.

If you are a small business in the process of designing or redesigning a website, ADA compliance might not be top of mind, but it should be.

There are reputable companies that can make sure your site is usable by all of your visitors. In many cases, simple best practices like adding alt-text to images, using sufficient contrast in your text, and observing page hierarchy will make your site compliant.

However, according to Tim Ostheimer, thinking of accessibility should be “less about just being legally compliant and more about trying to provide the best experience for anyone who’s going to visit your website.”

He continues:

“Generally, ADA compliance parallels best practices for web design and development — and optimizing for screen readers and mobile devices. This means that there’s no downside to ADA compliance other than the additional time spent planning and implementing it.

Many of the website features which are required for ADA compliance could end up being very useful to your average user as well, so there’s really no reason to ignore it. At the very least, think of accessibility as another level of optimizing for the best user experience.”

In 2020 and beyond, I think we can all agree on the importance of user experience, no matter whom it serves.

The internet today is a vital place of commerce, social interaction, customer support, government resources, research, and entertainment. To deny someone access to such benefits is to deny that person’s participation in the modern world.

On July 26th, 1990, President Bush signed the ADA into law, saying “this is an immensely important day — a day that belongs to all of you.”

Source: National Archives

He continued his remarks by noting the recent celebration of Independence Day.

President Bush went on to say: “We’re here to rejoice in and celebrate another Independence Day — one that is long overdue. And with today’s signing of the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act, every man, woman, and child with a disability can now pass through once-closed doors into a bright new era of equality, independence and freedom.”

Later, he calls for “the shameful wall of exclusion [to] finally come tumbling down.”

Now, 30 years later, new walls have gone up.

The government has again fallen behind in meeting the needs of its people in securing universal access to the internet — and these guidelines are, again, long overdue.

In the government’s stead, it is up to all businesses with a website, whether or not their digital space serves as a nexus to a physical one, to invest in making their content accessible to all users, regardless of what barriers might stand in the users’ way.

In turn, these new walls of exclusion will continue to come tumbling down, and people with disabilities will be allowed to fully participate in modern life.

Free: Assessment