Topics:

Content MarketingSubscribe now and get the latest podcast releases delivered straight to your inbox.

Real-life mad man, Howard Gossage is quoted saying, “people don’t read advertising, they read what interests them. Sometimes, it’s an ad.”

I think the Socrates of San Francisco was being a bit generous — it’s usually not an ad.

Then again, Gossage wasn’t fighting for the attention of consumers with ad blockers, instant notifications, and millions of terabytes of media at their fingertips.

However, in the era of branded content and inbound marketing, his point is more prophetic than ever.

When we write copy, we aren’t competing with other copy — we are competing with our persona’s favorite publications, television shows, social feeds, movies, and music.

We are competing with everything they would rather consume than what we just wrote to promote our businesses.

Now, I know you’ve heard this before. You get it. There is more content than ever and we need to write better copy if we want to stand out -- but we are failing, marketers.

Most content kinda sucks -- and it’s a shame.

Because when done right, content marketing can spur incredible business growth.

4 Non-Marketing Sources of Inspiration

I want to acknowledge that there is a ton of great marketing-specific content advice out there.

IMPACT’s very own Marcus Sheridan wrote a book called “They Ask, You Answer” that is one of my favorites and I highly recommend content guru Ann Handley’s “Everybody Writes” (See her at IMPACT live 18’).

Lessons from the golden age of copywriting also remain relevant.

The classic formula “create the problem, agitate the problem, and solve the problem” isn’t going out of style (I’m using it for this post) and you should always kill feature-heavy copy to highlight benefits.

But those two paragraphs are the last in this post that will mention advice specific to marketing or advertising.

Great copywriting can and should draw inspiration from divergent sources.

I firmly believe if we want to create business-changing content, we need to take a hard look at what our personas are consuming instead of our blogs, social posts, and landing pages.

These are 4 non-marketing forms of media that helped me learn to write better copy.

1. Journalism

In his hallmark writing how-to “On Writing Well,” William Zinsser wrote, “The most important sentence in any article is the first one. If it doesn’t induce the reader to proceed to the second sentence, your article is dead.”

Readers Follow the Lede

Long before the goldfish attention spans of today’s web readers, journalists understood an article lives or dies with the lead (or “lede” if you want to be old-timey).

A lead is the first 20 or 25 words of any article and how journalists hook their audience.

Leads can be as simple as a straight news lead that provides the reader a summary of all the most important facts.

This is commonly done for breaking news, like this example from today’s New York Times:

“A California man suspected of accessing and defacing numerous military, government and business websites, including that of West Point’s Combating Terrorism Center and the New York City Comptroller’s Office, was arrested Thursday on computer fraud charges.”

Although, in feature stories or non-hard news, journalists often employ other types of leads that may inspire you to write better introductions.

One such type is an anecdotal lead that uses narrative to draw you in.

Here’s a narrative lead from a 2006 pulitzer prize winning article written by Andrea Elliot in the New York Times:

“The young Egyptian professional could pass for any New York bachelor.

Dressed in a crisp polo shirt and swathed in cologne, he races his Nissan Maxima through the rain-slicked streets of Manhattan, late for a date with a tall brunette. At red lights, he fusses with his hair.

What sets the bachelor apart from other young men on the make is the chaperone sitting next to him — a tall, bearded man in a white robe and stiff embroidered hat.”

What makes this lead so strong is that it introduces the main tension of the story, that this young Egyptian bachelor must reconcile modern dating rituals with those of his traditional beliefs, without explicitly telling you all the summary facts.

It draws you in. You can’t help but want to keep reading.

When you’re writing meta descriptions, think of leads. What are the 300 characters you can write that will leave your audience with no choice but to click for more?

For some of your content, particularly educational content, that may mean the straight facts. Other content may be better teased with tension-filled narrative arcs.

Avoid Cliches & Jargon

Now, before any journalists call me out, I know my lead for this post is the much-maligned quote — but I like to think all rules are made to be broken.

If there is anything else editors hate, it’s cliches. Avoid them like the plague (yes, I did that on purpose).

In marketing, think ____ is dead, or ____ is king. No one really believes SEO is dead anymore and we get that content is king.

Also, eliminate all jargon.

We may say things like leverage, ten thousand foot view, and thought leader to each other, but our audience doesn’t. All jargon does is alienate them and demonstrate what a hard time we have talking like humans about our profession.

Don’t Ask “Yes or No” Questions

Another truism from journalists that may help sharpen your writing is Betteridge’s law.

Betteridge’s law states that any headline that asks a question can probably be answered no. It is designed to bring attention to the fact that if a journalist is using a question, it probably means they are trying to over sell what is in fact a pretty dull payoff.

If you were breaking the story that cancer has been cured, you wouldn’t write, “Have we found the cure for cancer?” You would simply write, “Cancer cured.”

Keep Betteridge’s law in mind when you are writing headlines or page titles. Otherwise, you risk alienating your audience with clickbait that only lets them know they shouldn’t click again.

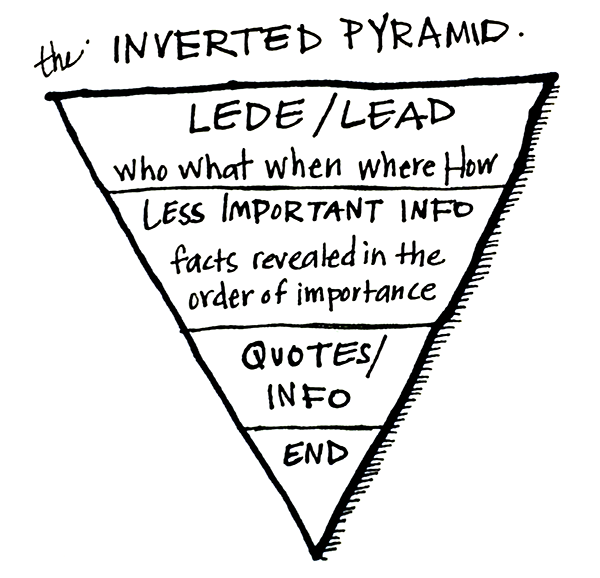

The Inverted Pyramid

And last, but not least, always remember the inverted pyramid.

Relevant for almost all media writing, the inverted pyramid states that the most important information in any article comes first, followed by gradually less important information throughout the story.

Don’t bury your lead or the most interesting thing about your content. Journalists are hard wired to use the inverted pyramid to give their stories structure and ensure that even if someone doesn’t make it to the end, they’ve gotten all that really matters.

The same should be true of your marketing content.

Think about that the next time you are writing a web page. If 50% of your users aren’t scrolling past the fold, is your hero copy communicating all that they really need to know?

2. Fiction

If we want our marketing content to resonate, it needs to tell a story.

An actual story. Something that moves from A to B to C to D, that has internal or external conflict, tension, closure, or hell, even a lack of closure.

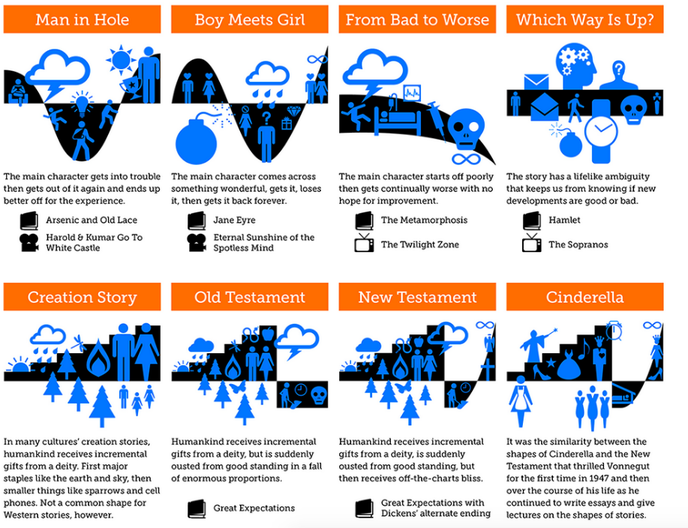

To tell better stories, we need to recognize when one is right in front of us. For that, I will defer to master sci-fi author, Kurt Vonnegut (“Slaughterhouse five” is his most known work).

During his anthropology graduate studies at the University of Chicago, Vonnegut noticed that the Bible’s New Testament and the enduring folk tale Cinderella followed nearly the same shape.

He posited that the “shapes” of the stories a culture holds most valuable reveal things about that culture, and submitted his findings for his master’s thesis.

While his professors rejected the thesis (because “it was so simple and looked like too much fun”), Vonnegut considered the shapes his “prettiest contribution to culture.”

I’ll let him explain:

These story shapes are everywhere.

Almost every episode of every sitcom uses “man in a hole.” Our favorite lovable cast of weirdos gets into a pickle, then they get out of it.

I would argue that the classic copywriting formula “create the problem...” is just the “man in a hole” story shape.

Rom-coms are always the “boy meets girl” shape — star-crossed lovers find each other, then lose each other, but luckily love’s eternal power always conquers all in the last five minutes.

Forget Cinderella — “Rocky,” “The Karate Kid,” and most sports movies always steal her shape.

Think about how you structure your marketing and sales stories.

Is it like this?

This is the way things are, now let me tell you why they will be a million times better.

We only tell our audience why our product or service is the greatest thing that anybody has ever conceived with no tension or conflict, but this doesn’t make your message persuasive -- it makes it sound like BS.

We cannot be afraid to introduce points of tension and conflict into our content.

People love stories because they love struggles that mirror their own. Human existence is a binary struggle between the way things are and the way we want them to be.

Effective copy can and should mirror this.

Or as I’ve heard Marcus Sheridan say (and I’m paraphrasing), “your content shouldn’t be just about the good, but also the bad and the ugly.”

Say the ugly that your competition is too scared to.

Explain who shouldn’t buy your product or service.

It takes guts, but you’ll wind up with better leads, more satisfied customers, and less churn.

3. Speechwriting

Aristotle taught his students that if they wanted to persuade an audience, they had to use three rhetorical appeals.

- Logos or logical appeals. These are supporting details and facts that bolster your point or argument (i.e. social proof, references, etc.). When I share all the ways Vonnegut’s story shapes work in popular media, I am making a logical appeal to convince you that you should try it with your content.

- Ethos or ethical appeals. These speak to your credibility to deliver that message. Extrinsic ethical appeals speak to your experience — I’ve driven results for clients with copywriting, so I feel credible to write about it. Intrinsic appeals are how well you deliver your message — if you think my writing sucks, you aren’t going to trust any of my writing advice.

- Pathos or pathetic appeals. This is very different from our interpretation of the word pathetic. These appeals speak to the emotions of the audience. I started this article strongly implying that your content may suck to appeal to your emotions of fear, “am I leaving money on the table because I’m not communicating my message well?” Instead, I may have actually appealed to your emotion of hate, “will this pompous marketer get off his high horse,” If so, thank you for hate-reading this long.

The world’s best speakers intrinsically use these appeals to hold attention, earn trust, and ultimately, inspire action.

Hours after Martin Luther King Jr. was shot and killed, Robert Kennedy stood on the bed of a pickup truck in Indianapolis to announce the news to a predominately African American crowd.

Despite concerns from campaign advisors about his safety, he delivered an improvised speech that is widely considered to be one of the most poignant addresses of modern politics.

This speech has taught me more about copywriting and rhetorical appeals than any other. I will resist the urge to go line-by-line but share select passages that highlight Aristotle’s appeals.

Logos

“For those of you who are black — considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible — you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization — black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another. Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.”

RFK is making a logical appeal. MLK stood for peace and nonviolence — to respond as a country to his violent end with violence is to betray the compassion and love he preached.

Ethos

“For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.”

To show the audience he understands their pain, Kennedy evokes the loss he felt when his brother John was killed by an assassin's bullet. His call “to go beyond these rather difficult times” doesn’t ring hollow because he too has struggled to move beyond deep despair.

Pathos

"My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: 'In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.'"

While nearly every line of RFK’s speech has an emotional appeal, it’s hard for anyone reading this beautiful passage not to feel universal human truths and emotions. We all try to forget pain, that one day, against our will, becomes perspective.

Kennedy is not merely using rhetorical appeals, but also rhetorical devices. These tools, developed by Greek masters of persuasion, are tried and true messaging techniques.

We are all familiar with metaphors -- Abraham Lincoln once said a political adversary, "dived down deeper into the sea of knowledge and come up drier than any other man he knew.” -- But there are many other devices that you may or may not be familiar with that can level up your copywriting.

To keep it in the Kennedy family, JFK loved rhetorical devices. Think "ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country." This is called antimetabole, and it’s a reversal of repeated words or phrases for effect.

Another, “let us never negotiate out of fear, but let us never fear to negotiate” -- This is called chiasmus and it’s a repetition of words and phrases in reverse order for effect.

If you want to try rhetorical devices to be more persuasive in your copywriting, here’s a list of 50.

4. Songwriting

There are few forms of art or media that evoke as visceral a reaction as music.

Songs that mean something to us stick to our souls. They become defining parts of who we are.

How many times do you hear a song and almost feel like you’ve stepped in a time machine to the first time that song meant something to you?

Because the experience is so personal, it is also wildly subjective from one person to the next.

A skilled songwriter creates this thing that is very personal to them and then releases it into the world to be interpreted.

Sort of like what we do as marketers, right? While everything filters through the lens of a brand’s needs and objectives, there are bits of us in all the creative and strategy we do, but I think, as marketers, we can learn a lot from how songwriters are able to create very personal works of art that somehow become universal.

When writing marketing and advertising copy, it’s so easy to try to create something universal.

No matter how much we keep our personas in mind, I think we all fight a voice in our heads that wants the copy or content to work for everyone. We don’t want to alienate anyone.

Great songwriters, however, understand all they can share is the truth of the story in their head and the more personal and specific they are, the more it gets at fundamental human truths.

As of writing this article, less than a week after it was released, the video for Childish Gambino’s “This is America” has 75 million views.

A still from Childish Gambino's "This is America" music video. (source)

For the sake of simplicity, the song basically has an A and a B part.

The A part is upbeat, has lots of melody, and jubilant singing buoyed by a choir of voices. The instrumentation includes gentle guitar, a danceable drum loop, and percussion.

The B part is dark and uncomfortable. There is no longer singing but Gambino now rapping with ad-libbed voices stabbing in rough vocalizations.

The instrumentation becomes something in the vein of southern trap hip-hop. There is bassy synths and the drum loop adds sub-divided hi-hats (they stay in the A part after the first B part).

Lyrically, the song is sparse.

The A parts are pretty much “We just wanna party, party just for you, we just want the money, money just for you (yeah)” or Ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh-ooh, tell somebody, you go tell somebody, Grandma told me, get your money, black man (get your money).”

The B parts are always “This is America, don’t catch you slippin’ up” repeated before simple phrases like “look how I'm geekin' out (hey), I'm so fitted (I'm so fitted, woo), I'm on Gucci (I'm on Gucci), I'm so pretty (yeah, yeah).

There isn’t much to it, right? Relatively simple lyrics over only 2 alternating musical themes --so why does the video have 75 million views?

Why is it seemingly the biggest pop culture moment that has happened in recent memory? Why is every news outlet and publisher trying to interpret, analyze, and discuss its significance?

The answer lies with Ernest Hemingway, who called his style of writing “the Iceberg theory.”

It’s a minimalist style that focuses on surface elements without explicitly discussing underlying themes. He believed the deeper meaning of a story (in this case, a song) should hide under the surface (like most of an iceberg), but be implicitly understood.

There is an adage in copywriting, that much like Hemingway’s 6 word story on a napkin, probably never happened, but persists because it contains an important lesson.

Legend says that famous ad tycoon David Ogilvy was walking down the street when he saw a homeless man with the sign, “I am blind, please help.”

He didn’t give him money, but rewrote the sign. When he walked by later, the man’s cup was overflowing. The sign now read, “It is spring, and I am blind.”

By adding “it is spring” Ogilvy gave everyone walking by the opportunity to attach their own connotations, experiences, and stories about spring to the sign.

That is what Gambino did.

Childish Gambino’s song has 75 million views because the imagery in the video and his SNL performance show a glimpse of what is under the iceberg of those simple A and B parts.

A still from Childish Gambino's "This is America" music video. (source)

The parts are suddenly exposed as a pointed narrative about his experiences as an African American. The juxtaposed sections take on entirely new meaning as a critique of the dissonance between the perception and reality of his experiences, and how pop culture distracts us from turmoil.

He is communicating a very specific and personal truth with “This is America,” but its simplicity leaves enough below the iceberg’s surface for everyone to bring their individual perceptions of our country’s current political turmoil to their experience with the song.

It’s an uncomfortable, but profound song and video that speaks to a very universal discomfort happening in America right now.

Excuse the Cliche, But: Think Outside-of-the-Box

Don’t write generic marketing copy and content.

The next time you write copy, ask yourself, “is this an ad, or is it interesting?”

Order Your Copy of Marcus Sheridan's New Book — Endless Customers!